Dialogue: Iñaqui Carnicero, co-curator Spanish Pavilion la Biennale di Venezia. Architectem Magazine

The Spanish Pavilion was awarded a Golden Lion at this year’s Venice Biennale, featuring a new type of architecture that emerged in the country after the financial crisis.

Under the title “Unfinished”, the exhibition curated by architects Iñaqui Carnicero and Carlos Quintáns consists of nearly 67 proposals and 7 photographic series presenting answers to the problems arising in Spain after the housing boom post-crisis. The inherited situation has led to many architectural studies to reflect on the passage of time in architecture and to respond against the excesses of the past.

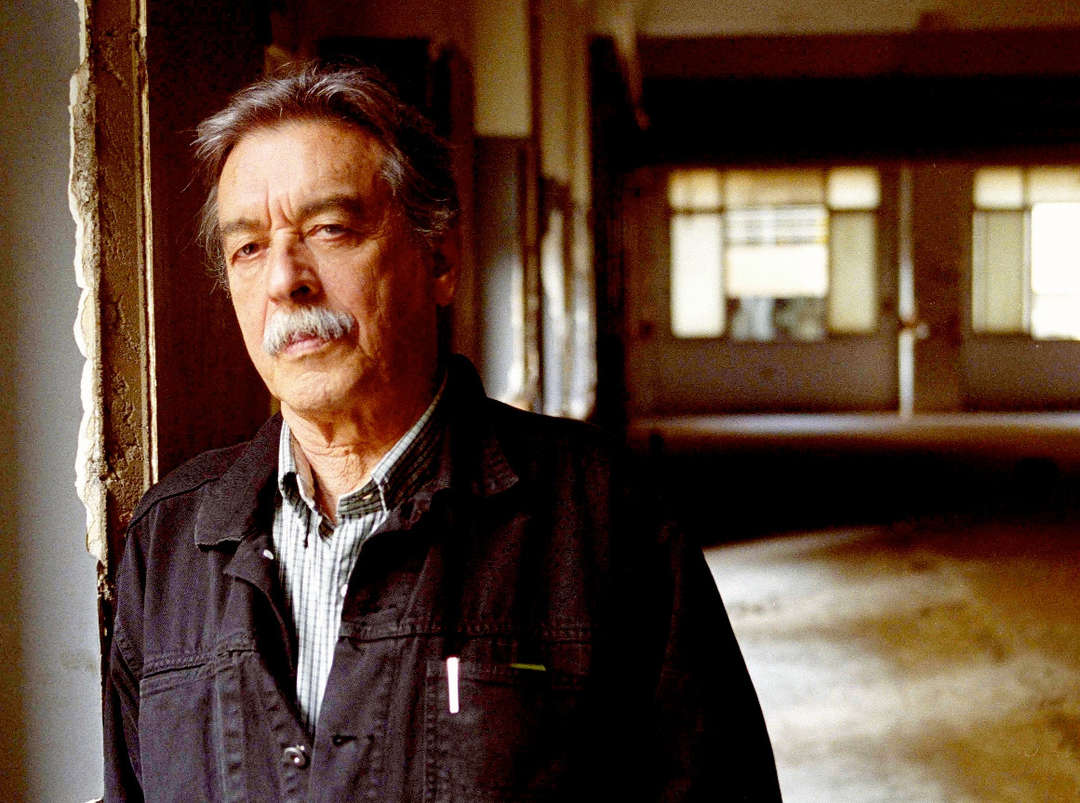

Exhibition curator Iñaqui Carnicero is an Architect and has served as a visiting Professor at Cornell University. He has been recognised with numerous international awards such as the Design Vanguard Award, AIANY Housing Award, Emerging Architects Award, FAD and COAM Award.

The exhibit is divided into four areas:

Photographic series – highlighting otherwise hidden situations for visitors to reflect on the outcome of Spain’s construction frenzy and the affect of the financial crisis.

Selected Works – Displayed in the side rooms, featuring projects that deal with strategies that architects put into play as a response to these situations. These projects are further catalogued under the titles: Consolidate, Reapropiation, Adaptable, Naked, Perching, Infill, Reassignments, Guides, and Pavements.

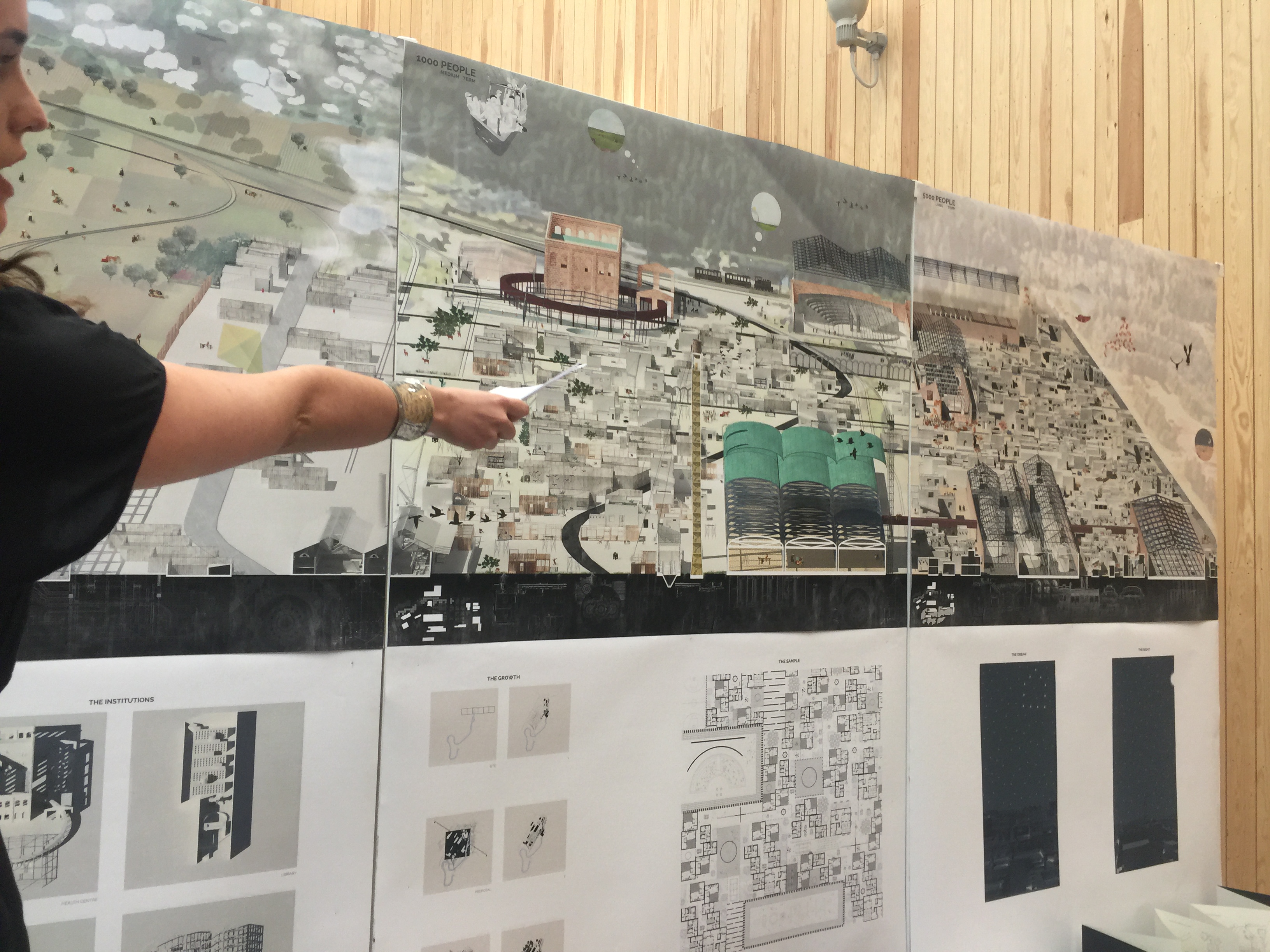

Selected entries – Presenting selected projects from an open competition aimed at searching for unpublished projects responding to the proposed theme.

Interviews – Behind the central space and between the side spaces is a continuous projection of interviews, recording comments by renowned architecture personalities on “Unfinished” as well as about Spanish architecture. Speakers include Amale Andraos (Dean at Columbia University), Kenneth Frampton (Full Professor at Columbia University), Sarah Whiting (Dean at Rice University), Andrea Simitch (Associate Professor at Cornell University), Sou Fujimoto (Architect), Barry Bergdol (Ex curator MoMA), Val Warke (Associate Professor at Cornell University), Jorge Silvetti (Full Professor at Harvard GSD), Nader Tehrani (Dean of Cooper Union), Meijeen Yoon (Chair MIT) and Martino Stierli (Chief Curator MoMA )

ARCHITECTEM met with Iñaqui at the vernissage to discuss the exhibition and the challenges contemporary designers face in Spain – below is a condensed version of the conversation

Unfinished seeks to direct attention to processes more than results in an attempt to discover design strategies generated by an optimistic view of the constructed environment. The exhibition gathers examples of architecture produced during the past few years, born out of renunciation and economy of means, designed to evolve and adapt to future necessities and trusting in the beauty conferred by the passage of time. These projects have understood the lessons of the recent past and consider architecture to be something unfinished, in a constant state of evolution and truly in the service of humanity. The current moment of uncertainty in our profession makes its consideration here, especially relevant.

![]() Let’s begin with the concept

Let’s begin with the concept

IC This year Alejandro Aravena invited curators of all the national pavilions to respond to what we think is the major issue that architecture has been suffering in recent years. For us in Spain, it was very obvious; the problem has to do with the fact that when we benefited from a period of economic wealth, we started building many public and private buildings, without reflecting too much on necessity. After the economic crisis, some of these structures that were under construction remained unfinished, because the clients did not have money and resources to maintain them. What we have in Spain right now is a collection of contemporary buildings, what we call ‘contemporary ruins’, that exist all over and nobody is taking care of. So the idea of the pavilion is on one hand reporting these situations, these unfinished constructions but at the same time giving a positive perspective. By inviting seven photographers in the central space we are showing the work of seven people who have been documenting these ruins and it has a certain beauty of showing things that are meant to be hidden. For us the beauty of the process is the opportunity it leads you to find other tools or strategies that can be used to solve things. On the one hand, we are reporting the situation in the central space, and at the same time we are showing on the sides, solutions.

![]() The catalogue posits “The selected projects show the architects response to the economic and construction crisis over the past years in Spain through virtues that can become strategies or creative speculations which are capable to subvert the past condition into a positive contemporary action.” Do the ‘contemporary ruins’ act as dynamic case studies in the quest for solutions?

The catalogue posits “The selected projects show the architects response to the economic and construction crisis over the past years in Spain through virtues that can become strategies or creative speculations which are capable to subvert the past condition into a positive contemporary action.” Do the ‘contemporary ruins’ act as dynamic case studies in the quest for solutions?

IC They became the tool to report this situation. So as solutions to the unfinished projects, the projects on the sides consider the built environment as part of the strategy and reflect on the amount of architecture needed to be produced in order to solve the problem and to activate these abandoned constructions.

![]() The strategies thus proposed are specific to the local context; can they be universally applied?

The strategies thus proposed are specific to the local context; can they be universally applied?

IC I think it can be universally applied, I mean this problem of incomplete and unfinished construction or this idea of reflecting on the factor of time in architecture is relevant for us, its very contemporary for us, but we can find it in other countries, other contexts and I think it’s a critical global issue. It brings attention to the fact that we have to be aware of the resources we have and to balance the amount of resources we put on the table to solve problems. Actually I think it is an opportunity.

![]() Being an active academic, are these issues of reassignment, adaptability and re-appropriation a focus in the studios you teach?

Being an active academic, are these issues of reassignment, adaptability and re-appropriation a focus in the studios you teach?

IC Defiantly. At Cornell these past three years, these have been the major topics we have been working on in the studios as well. I like to always put students under constraints. Certain constraints are often given by the site, by the political situations, and sometimes defined by the history of a place. By reducing the amount of elements students can use, they are forced to improve their creativity.

![]() In the prevailing economic and political environment do you anticipate architects bearing increasing responsibility to provide solutions for unfinished and existing projects?

In the prevailing economic and political environment do you anticipate architects bearing increasing responsibility to provide solutions for unfinished and existing projects?

IC In Spain it’s happening, because of the lack of investment for new buildings many offices are inventing this new strategy; adding to or removing from things that already exist, sometimes thinking about the evolution of a building by proposing solutions but then also thinking about what will happen in another 20 years. So this a new way of thinking about design in Spain, that I think could be extended to other countries.

![]() Will this global movement affect the way we define star architects or style specific architectural design?

Will this global movement affect the way we define star architects or style specific architectural design?

IC Of course, 8 years ago in the model we had, the masters were star architects defining their own brand. They were fighting to restore an old language and then going on to define what they thought was their unique language. Now these proposals are more related to offices, where young architects are less interested in defining their own brand and more in using the tools they learn in school in order to produce and improve living conditions by measuring the amount of new architecture they need to produce. I think the identity of the architect is still there, if you see these 55 projects you can see very different approach. And they identify very different interests. I’m not saying that the architect, the creativity of the architect is not present anymore. It’s an opportunity to be more creative with less tools. I’m very positive about the near future and this shift, I think, is going to improve things.

The exhibition at the Venice Biennale will remain open up till 27 November 2016.

The Spanish Pavilion curated by architects Iñaqui Carnicero and Carlos Quintáns

The Spanish Pavilion curated by architects Iñaqui Carnicero and Carlos Quintáns