pied-à- terre

noun \pē-ˌā-də-ˈter, -ˌā-dä-; ˌpyā-dä-\

A small house or apartment in a city that you own or rent in addition to your main home, where you stay when visiting that city for a short time French for "foot on the ground"

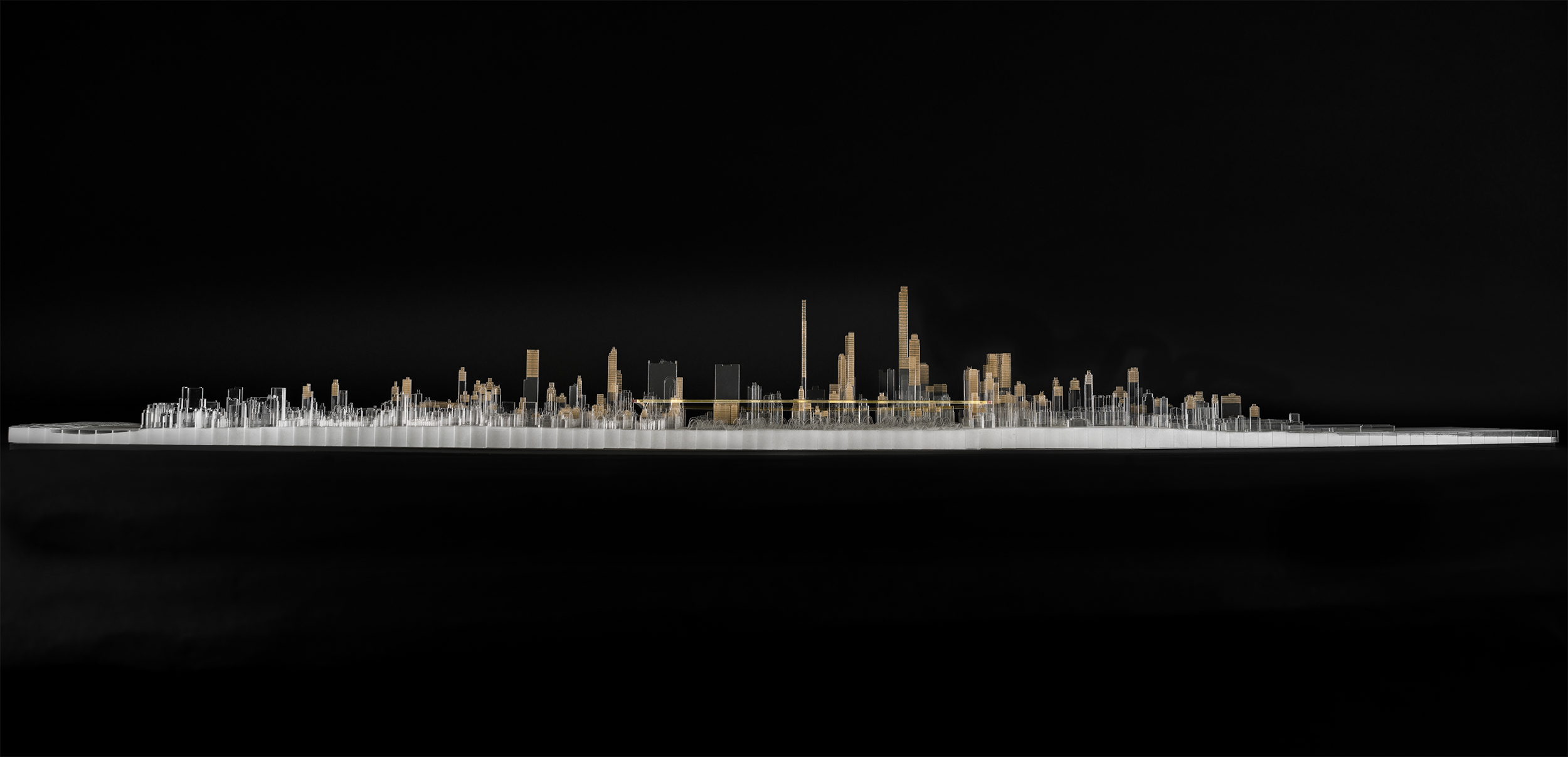

Owning a piece of New York or “putting a foot in the city” has become a shared aspiration for the global rich, from traditional American and European buyers to cash-flush Russians, Chinese, Middle Easterners and Brazilians. In recent years, the demand for these super-elite luxury apartments has increased dramatically, creating a whole new typology of skyscraper, the “superslenders”, which are rising on the New York skyline.

When people purchase these palatial residences in the sky, they are not simply buying a home but rather a lifestyle and a status, both of which don’t actually require one to live in the building. The competition for these so called trophy apartments therefore arises not from a necessity for dwelling but from a battle of the egos; they are showrooms, not hearths.

As is often the case with trophies, they are left up on a high shelf to collect dust, and the proliferation of these properties have left large areas of the city “owned but not used”. Ghostly towers stand with dark windows, seemingly abandoned but ironically “SOLD OUT”. According to the New York Times, “In one part of [Midtown], between East 53rd and 59th Streets, more than half of the 500 apartments are occupied for two months or less. That is a higher proportion than in resort and second- home communities…Between 2000 and 2011, the number of Manhattan apartments occupied by absentee owners and renters swelled by more than 70 percent, to nearly 34,000, from 19,000.”

The problem with this is that not only is valuable real estate essentially wasted, the high demand makes these buildings more profitable to construct than badly needed affordable housing that would address the city’s rampant housing shortages. Some have suggested a Pieds-à- Terre tax to deter potential buyers, but the logic behind this is flawed, as extra costs will only serve to make these properties seem more elite, and therefore, more desirable. Other strategies such as forced rental will similarity have difficulty achieving the desired results as owners will simply set up dummy renters that keep the space unoccupied.

The Golden Loop represents a satirical perspective on the extravagance and wastefulness of these real estate practices. As opposed to taxation or regulation, the project will engage these properties directly by providing access, both visually and physically, to these otherwise forbidden domains, blurring the lines between what is public and private. The goal of the project is to reincorporate the territories lost to the insatiable appetite of the super-elite back into the public sphere by allowing universal access to the amenities that they hoard. Through the act of occupation instead of inhabitation, we are left to contemplate how these two vastly different worlds can exist simultaneously, oblivious to each other’s existence.